For current university students and recent graduates, preparing for a trading interview will involve a substantial amount of industry and company-specific research. The candidate must, at a minimum:

1. Know the Industry.

2. Know the company and its primary business.

3. Have a sense of the immediate evolutionary challenges the firm is facing.

4. Know the people they will be speaking with, their backgrounds, the markets they inhabit, and the products they trade.

5. Know as much as possible about how the market is traded at the target firm, and how the candidate’s skills make them a good match for that product.

6. Prepare for some of the obvious questions they should expect to be asked.

7. Prepare for the programming & data science requirements of the job.

Know the Industry

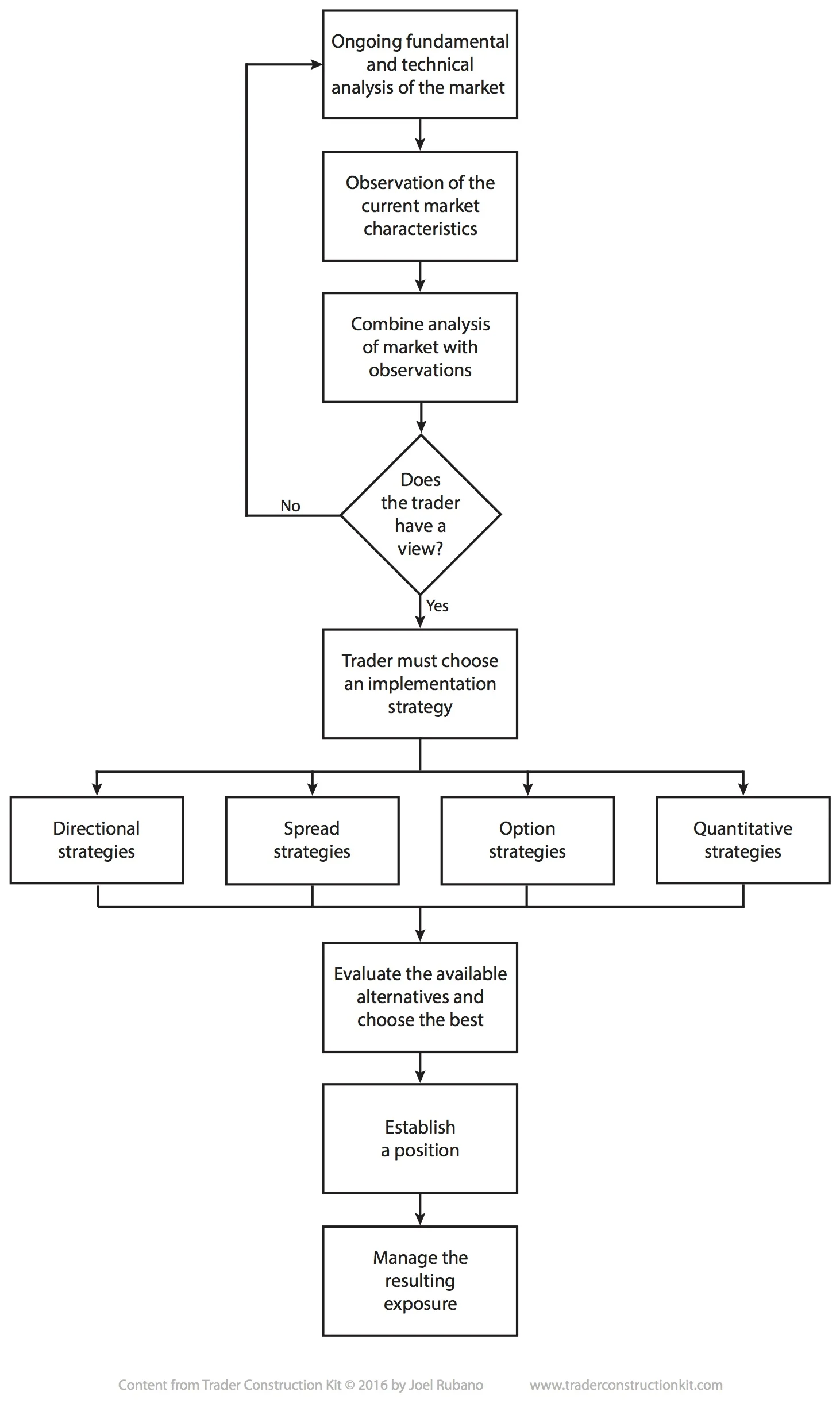

The opportunities available and the types of business transacted are, to a great extent, determined by the evolutionary state of the industry. Early-stage markets offer the most opportunities for rapid advancement for candidates with an entrepreneurial mindset and a willingness to innovate in an evolving operational environment. Fully-evolved markets have established career paths, with measured progression based on the mastery of and deployment of established knowledge sets. A candidate needs to know the evolutionary state of the industry they are targeting to calibrate their expectations of the potential career progression available to them, and to understand the company’s expectations of their initial and to-be-developed skill set.

Know the Company

In Trader Construction Kit I focus the majority of the second chapter on describing the market activities of four categories of market participants: Hedgers, Merchants, Financials and Speculators. Each category participates in a market for specific reasons, engages in different types of risk-shedding, risk-modifying, or risk-taking activities, and hires traders will different skill sets to implement their business plan. A candidate must know what type of firm they are speaking with and understand the basics of their core business and corporate culture.

Have a Sense of the Immediate Evolutionary Challenges the Firm Faces

There is a lot of change going on in the world of finance and trading, at the moment. The Europeans are grappling with the implications of MiFID II, the British banks are trying to plan for the continuity of their business under all of the possible permutations of Brexit, the Americans are navigating a sea change from an environment of increasing regulation to one of possibly decreasing oversight, and everyone is dealing with the accelerating impacts of technology (AI, algorithms, blockchain, cryptocurrencies, etc.) on their core businesses. While a candidate will not be expected to be a subject matter expert on every last regulatory nuance, they will be expected to have a general sense of what is coming and how it may impact the business unit they are interviewing with.

Know the People and the Markets

In a Google and LinkedIn world there is no excuse for a candidate not having a basic familiarity with the backgrounds of their interviewers. The person arranging the schedule will generally provide a list, if asked nicely by the candidate. The candidate must know each interviewer’s position within the company to understand their function, their implied perspective, and develop a sense of what sorts of questions to anticipate. A risk manager with a Masters in physics and a PhD in quantitative finance will have entirely different concerns and ask entirely different questions than a proprietary trader with a background in the crude oil pits and scars on his knuckles. The candidate must find a way to be relatable to both.

A candidate should expect to speak to the head trader, their lieutenants (one of whom will probably be the hiring manager), a junior person to provide a skill-set comparison with a near-peer, and potentially members of the risk, analytics, and compliance groups. If that sounds like a lot of people, it is, and an aspiring trader should expect a full day of half-hour to hour long conversations with one or two people at a time. It can be difficult to maintain focus, but in the vast majority of cases the candidate must leave a positive impression on every interviewer and really shine with the one or two shot-callers they meet.

Know How They Fit In as a Candidate

In Chapter 1 of Trader Construction Kit (which is available here), I list the positive characteristics of successful traders and the negative traits of unsuccessful ones. The candidate must accurately assess their unique strengths and weaknesses and how they apply to the demands of the trading environment at their target firm. If the candidate wants to build bleeding-edge algorithms at an industry-leading quantitative hedge fund, they had better really know how to code or they will be laughed out of the room. Ditto for an unassertive pit trader, a non-mathematical option trader, a disorganized market-maker, or an indecisive directional trader. There is no shame in being a poor fit for a particular job at a particular firm. There is a tremendous amount of shame in showing up for the interview either not knowing that, or attempting to pass oneself off as something they are not.

Prepare For the Obvious Questions

A current student or recent graduate with little to no practical trading experience to be quizzed on should expect the standard probability and logic based questions. Read up on the Monte Hall question, basic conditional probability problems, and (my personal favorite) the TV Question. The candidate should expect questions about sports played, team activities, and their propensity for gambling and other risk-taking behaviors. In lieu of actual experience, the traders will want to see that the candidate can logically process information and make decisions quickly under stress. At some firms it is very fashionable to manufacture an artificially stressful environment to test the candidate, others will prefer a more collegial, conversational approach.

The candidate should also have at least a superficial familiarity with the benchmark informational resources for the market, both in terms of the standard educational texts and the book/blog/site/news of the moment that everyone is currently reading or talking about. Giving a blank stare to an interviewer who name-checks Nassim Taleb or references The Big Short is a big negative. A list of some common resources that an aspiring trader can investigate to help them prepare for an interview (Trader Construction Kit among them) can be found here.

Prepare For the Programming & Data Science Requirements

In 2017 the incremental must-have skills on the trading desk are programming and data science. Python is far and away the platform of choice for most on-desk development, and its large library of pre-existing code modules like NumPy, Pandas, and Matplotlib make it relatively easy to manipulate data and produce usable results. Firms that employ AI, Deep Learning, or any sort of non-traditional data set analysis will employ significantly more esoteric and powerful tools. While it is true that most of the heavy programming work will be done by highly specialized CS and Data Science graduates, on a going forward basis not being able to code will become akin to not being able to read or write. I believe that this evolution will happen very quickly, and that as trading becomes increasingly machine driven, the person most able to transform data into actionable information will be the person seen as adding the value to the organization. One relationship that will not change in the future is that adding value = getting paid.

Fluency in Python and an aptitude for Data Science will also serve as a valuable safety net in case the candidate is not hired as a trader. It is very common for even a top-notch candidate from a strong academic program to be hired into the firm in a non-commercial support position, either as an assistant trader, analyst, risk-manager or deal structurer. Support functions typically serve as a combination apprenticeship and extended interview for the trading desk. Making the transition from a support role to the trading desk presents its own set of unique challenges, which will be the subject of a follow-up post.